Between De- and Hyper-Politisation: The evolution of Russian authoritarianism

In the 21st century, Russia has transformed into a typical authoritarian state, where political representation of its citizens has become increasingly nominal, relying on an unspoken agreement with the regime: in exchange for abstaining from active political engagement, citizens are promised stability and access to economic prosperity. Today's Russia is often described by experts as nearly totalitarian or (neo)fascist, denoting the escalation of repression, glorification of violence and war, and aggressive denial of the existence of neighbouring countries and distinct ethnicities. However, key attributes of typical totalitarian regimes such as an all-encompassing ideology, mass party system, and widespread political mobilisation seem to be absent in Russia. How can we characterise such a regime, and what is the nature of its evolution?

Over the past two decades, the Putin regime evolved through three distinct phases. In the 2000s, it embraced a form of soft authoritarianism, relying on the depoliticisation of the population, prioritisation of economic efficiency, and selective limitation of political freedoms. In the 2010s, the regime faced a gradual politicisation of society, to which it responded with a counter-politicisation approach. However, as these measures proved insufficient, the regime resorted to external aggression as a means to achieve deeper mobilisation and facilitate radical transformations of both the regime and society. This path from depoliticisation to hyper-politicisation is not unique among authoritarian regimes, but in Russia, this process remains ongoing and is far from complete.

Stability and two types of uncertainty

In his book 'The Two Logics of Autocratic Rule' (2023), Johannes Gershevsky examines the evolution of 45 Asian regimes after World War II and puts forth the argument that despite their apparent diversity, authoritarian regimes adhere to one of two fundamental logics: the logic of depoliticisation or the logic of hyper-politicisation. These fundamentally enable them to maintain stability. However, it is essential to recognise that stability in authoritarian regimes may not necessarily translate to stability for society as a whole.

According to Gershevsky's analysis, building on Adam Przeworski's ideas, the primary distinction between authoritarian and democratic regimes lies in their approach to uncertainty. Democratic regimes are characterised by organised uncertainty, where robust political institutions, procedures, and norms enable the resolution of uncertainty through well-defined rules. While the outcome of elections remains uncertain, defeat for a party or candidate is not fatal, as the established rules constrain the winner's power, and the losing side has an opportunity to win in future elections.

On the other hand, authoritarian regimes rely on the principle of organised certainty: the main objective of political institutions is to facilitate the manipulation of the political process to ensure those in power can extend their rule for as long as possible. Instead of organising uncertainty, they orchestrate certainty. Elections in contemporary Russia, as well as in other authoritarian countries, serve as a vivid illustration of this principle: their purpose is not to ascertain the will of the people but to reaffirm the permanence of those in power. This certainty is presented to society as a guarantee of stability.

However, it must be noted that while autocrats and their coalitions strive to eliminate uncertainty for themselves, their actions inadvertently give rise to a different kind of uncertainty, for example regarding their policies. In democracies, this uncertainty is mitigated by public scrutiny of pre-election and party promises, as well as the presence of numerous veto players. However, in authoritarian regimes, these checks and balances are absent. A glaring example of this is seen in Russia's invasion of Ukraine, where, despite warnings from American intelligence, no one in Russia, be it society or elites, believed that war was a possibility just a month before it occurred. The decision to initiate the conflict was made by a small, secretive group detached from society and even the main elite groups. The second type of uncertainty is related to the fact that, by eschewing representation, authoritarian regimes deprive themselves of crucial information about the actual sentiments of society. As a result, under the guise of certainty, autocracies often plunge countries into acute crises.

Nevertheless, many authoritarian regimes manage to sustain this certainty and their own stability over extended periods. The foundation of their stability rests on three main pillars: the ability to maintain legitimacy in the eyes of the population; the suppression of their competitors (the opposition); and the cooptation of elite groups. It is precisely these instruments that are organised differently within the framework of the two aforementioned logics — the logic of depoliticisation and the logic of hyper-politicisation.

Logic of Depoliticisation and Logic of Hyper-Politicisation

The logic of depoliticisation is a characteristic of authoritarian regimes during periods of economic prosperity. Economic stability, social protection, and security, which citizens value and attribute to the ruling coalition and its leader, provide this type of 'performative' legitimacy. Such a regime appears effective in the eyes of the population. Depoliticisation relies on the relative satisfaction of the population with the existing status quo and their disinterest in political participation. As a result, people tend to tolerate the manipulations of elections, terms, access to elections, and restrictions on press freedom. Additionally, the ruling coalition can effectively coopt elite groups by controlling access to economic rents. Although a 'ruling party' usually exists, the primary role in the mechanisms of cooptation belongs not to the party itself but to informal institutions such as patronage networks and clientele systems.

A state that possesses ample resources to distribute rents and uphold a satisfactory standard of living for its citizens typically does not require a grand national idea or extensive repressive measures. Instead, the selective and mild repression of the opposition are usually enough to marginalise it. This repression often seems justified to the majority of citizens as it is framed within the context of maintaining order and stability. This type of regime is also referred to as 'competitive authoritarianism.'

The logic of hyper-politicisation operates on an opposite basis and in a different direction. It comes into play when 'performative legitimacy' is absent or insufficient. This occurs when the economy experiences stagnation or insufficient growth, making it challenging to distribute benefits widely among the population, which may lead to a decreased belief in the regime's effectiveness among citizens. In such cases, or as a supplement to 'performative legitimacy,' the regime relies on ideological legitimacy. The continuous stay in power of the ruling coalition and its leader is explained by various arguments that interpret national interests and threats to the nation's well-being and security.

Hyper-politicised autocracies rely on mobilising the masses since they lack the ability to distribute material benefits widely. Instead of enriching their citizens, they focus on governing their hearts and minds. In such regimes, ideology plays a crucial role in legitimising their rule. It may not necessarily be a classical all-encompassing ideological system like communism or fascism; it can be nationalism, ethnocentrism, or religion. Ideology also serves as the cornerstone of such regimes because it justifies the repression of opponents in the name of achieving the regime's proclaimed goals of the 'common good,' which would otherwise be threatened. At the same time, elite cooptation usually occurs through formal channels, such as a mass party. This party becomes a key instrument in maintaining unity among the ruling elite

North Korea is an example of an extremely stable hyper-politicised autocracy that has maintained its rule for decades, despite internal crises, external pressure, and changes in leadership. However, this is an extreme case. In general, depoliticisation and hyper-politicisation are two systems of complementary institutions. In one case, it includes performative legitimacy, relying on high levels of trust in the regime, the absence of ideology, informal mechanisms of elite cooptation, and low levels of repression. In the other case, it entails ideocratic legitimacy, assuming belief in the ideology's absolute prioritisation of national interests, broader and harsher repression of dissenters, and a growing role of formal institutions in coopting elite groups.

Authoritarian regimes may occasionally incorporate elements of both these institutions, but, in general, certain circumstances push them, in the pursuit of self-preservation, to shift from one logic of legitimacy and maintaining stability to another.

Three periods of Putin's authoritarian evolution: Depoliticisation in the 2000s

Over the past two decades, Russia's political history can be distinctly divided into three periods. The first period began in the early 2000s when Vladimir Putin assumed power, leading to the establishment of a depoliticised personalistic autocracy in Russia. Following the protracted crisis of transformation in the 1990s, Stabilisation and economic growth provided the regime with legitimacy in the eyes of a significant portion of the population. Through targeted repression, exemplified by the cases of figures like Khodorkovsky, Gusinsky, and Berezovsky, the regime rid itself of the most dangerous competitors, the oligarchs. At the same time, it offered other individuals informal cooptation rules based on their willingness to distance themselves from politics, essentially embracing depoliticisation as a strategy. Meanwhile, major independent media outlets were nationalised or handed over to corporations loyal to the new government. As a result, independent political actors faced limitations in accessing these outlets and, consequently, faced restrictions in participating in elections. Meanwhile, the newly formed 'United Russia' party served as a means of coopting (mostly) regional elites. At the federal level, individuals with strong ties to Vladimir Putin, often stemming from long-standing relationships such as the cooperative 'Ozero' and former KGB colleagues, gained informal influence and control over major corporations and assets.

During the initial decade of Putin's rule, a noteworthy aspect of depoliticised authoritarianism was the absence of a prominent ideology. The regime declared a commitment to reformist (developmentalist) goals and democratic principles, while emphasising the value of 'stability' and a hierarchical management system ('power vertical'). It occasionally encouraged pro-government activism, exemplified by initiatives like the 'Nashi' movement. However, generally speaking, the regime did not actively seek to ideologically indoctrinate the population as a significant part of its agenda. Instead, it strategically cultivated contempt and distrust towards any ideology as essential elements of its depoliticisation strategy. All of this was reinforced by high rates of economic growth and noticeable improvements in the social well-being of Russians.

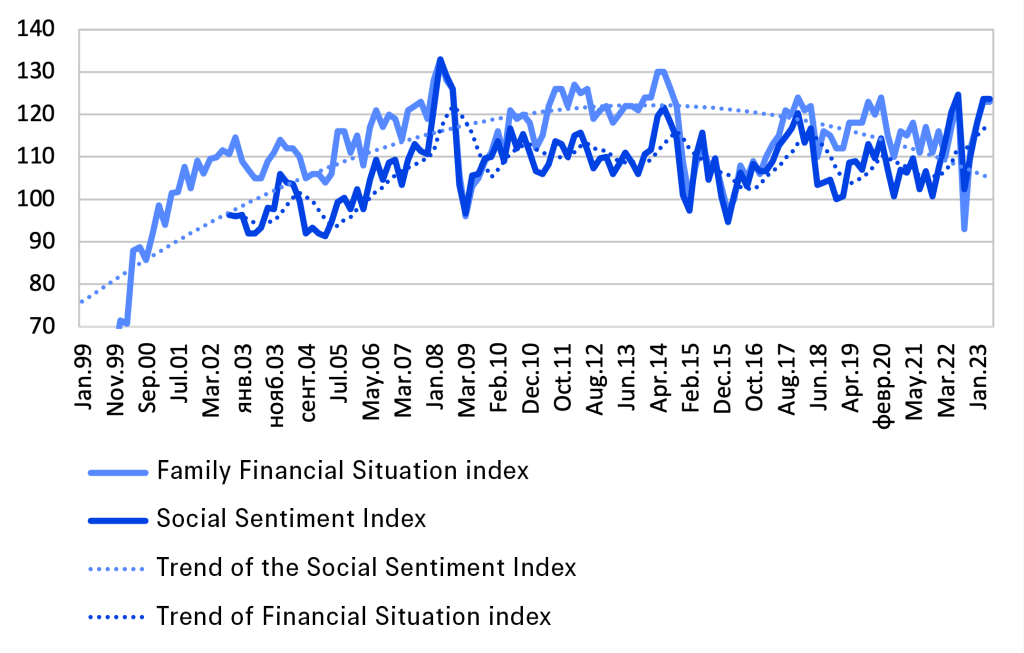

Social Sentiment Index and Family Financial Position Index, Levada Center, 1999-2023

Source: Levada Center

The situation started to shift after the 2008-2009 crisis, which significantly weakened the perceived connection between Putin's regime and economic prosperity in the eyes of the population. In the 2010s, social sentiment indices, which had been steadily increasing by 25-30 points throughout the 2000s, plateaued and fluctuated around the values achieved by the end of the 2000s. Moreover, the pace of economic growth experienced a sharp decline, dropping from 7% in the first period (1999-2008) to a mere 0.7% in the subsequent decade.

Competitive politicisation in the 2010s

Against this backdrop, society witnessed a notable increase in politicisation, highlighted by the mass protests of 2011-2012. . A new generation of Russians demanded participation in politics and challenged the established status quo of the 2000s. In response, the state imposed further restrictions on political freedoms and cracked down on individual protesters. Despite the marked economic slowdown, the substantial revenues generated from energy exports allowed the government to fulfil the portion of the 'social contract' centered around depoliticisation: ensuring stability, security, and access to essential social goods for a broad segment of the population. Notably, pensions continued to be steadily increased (with pensioners making up over 35% of Russia's adult population).

Nonetheless, over the following decade, both society and the authoritarian regime experienced a gradual shift towards greater politicisation. As Putin's new presidential term commenced, discussions about 'traditional values' that set Russia apart from the West gained momentum. The annexation of Crimea and the war in eastern Ukraine triggered partial mobilisation of the population, resulting in heightened tensions with the West and intensified anti-Western rhetoric in official discourse.

During the latter half of the 2010s, alongside targeted repressions and the implementation of restrictive laws, new networks of political activism emerged in major cities. Independent media shifted to the Internet, utilising social networks as a crucial tool for building a new media environment and fostering further politicisation. This trend led to growing polarisation: while older generations continued to rely on regime-controlled television, younger demographics sought information from independent online media sources. From 2017 onwards, mass street protests resurged as a means of political mobilisation, particularly gaining traction among the younger population. Alexei Navalny emerged as a central figure, galvanising a youth opposition movement, and his YouTube channel audience peaked at 10 million people. A culmination of this process was marked by the failed assassination attempt on Navalny and the release of a film exposing Putin's alleged palace, which was viewed by tens of millions of Russian citizens.

During this time, the official ideological discourse also underwent a process of radicalisation. A mixture of conservative values, anti-Western sentiments, militarism, and the cult of the Great Patriotic War did not create a cohesive ideology but rather delineated a system of value narratives united by opposition to the West and Western 'liberalism.' Essentially, 'Putinism' in the late 2010s emerged as a significant representation of 'anti-liberalism' ideology, illiberalism, which significantly strengthened its position worldwide. In domestic policy, the concept of internal and external enemies became increasingly crystallised – a hallmark of highly politicised autocracies, according to Herschel. Such regimes construct a clear 'frontline' that divides friends and foes. Their categorisation of 'foes' took on increasingly tangible characteristics: agents of hostile influence, Western-funded NGOs aiming to undermine 'traditional values' and the foundations of social 'stability,' and even the very existence of Russia.

In conclusion, during the decade between 2011 and 2021, Russia witnessed two distinct and competing processes of politicisation within society, ultimately contributing to its growing polarisation.

Hybrid hyper-politicisation and its future

The full-scale invasion of Ukraine, which has evolved into a protracted military conflict, has become a tool for authoritarian hyper-politicisation. This hyper-politicisation is marked by a sharp escalation of public mobilisation, repression, and violent indoctrination. Amid the war, any dissenting views of disagreement with the declared national interests are openly construed as acts of betrayal and sabotage. Unlike in the past, where repression primarily targeted political activism, it has now extended to persecute individuals who express their opinions publicly. Matters that were once considered private affairs of individual citizens have now been politicised and interpreted as acts against the regime: social media posts and even personal conversations are now grounds for administrative and criminal prosecution. The state education system, including schools and universities, actively propagates ideological indoctrination. Expressing dissent towards the ongoing war has become a pretext for the 'social exclusion' of artists, scientists, or athletes. The sphere that was one ‘private’, which remained relatively untouched by the depoliticised regime of the 2000s, is now subjected to the aggressive expansion of the regime.

The war has allowed the regime to shift its focus further from performative legitimacy to ideological legitimacy: as long as Russia is surrounded by enemies, people may not only tolerate the lack of familiar comforts and endure hardships, but also demonstrate a willingness to make sacrifices, even laying down their lives for their country.

Undoubtedly, the logic of hyper-politicisation is the central trend of Putin's regime in this new period. However, economic stability still remains an important pillar of support. Despite the ongoing war, mass mobilisation, and significant human losses, there are extensive 'comfort zones' within the country where the war's impact is not strongly felt. The 'depoliticised' territory remains quite substantial. Repression has not yet become widespread, and the establishment of a mass ruling party that institutionalises mechanisms of elite cooptation has not been pursued. Calls from radicals (z-patriots) for broader mobilisation, imposition of martial law, reintroduction of the death penalty, and a significant increase in state involvement in the economy have so far been ignored by the Kremlin.

This heterogeneity or hybrid hyper-politicisation aligns with the vagueness of the ideology of illiberalism which serves as its driving force. Illiberalism lacks a clear blueprint for achieving economic prosperity and largely relies on clientelism, hedonism, and corruption as means of fostering loyalty rather than relying on 'belief in ideals.'

Nevertheless, this dual nature of the regime is not an isolated phenomenon. Unlike North Korea, where hyper-politicisation allows the regime to retain control over society even amid economic degradation and famine, the Chinese model combines strict ideological constraints and extensive political repression with a focus on ensuring high rates of economic growth and welfare. This approach demonstrates a significant level of regime responsiveness as it seeks to meet social expectations, which remains a crucial pillar of its legitimacy. As Herschel notes in his book, China represents a unique example of the synthesis of the two models of legitimacy in Asia. However, unlike China, Russia's hybrid hyper-politicisation is not based on the ideology of developmentalism and high economic growth but on substantial revenues from commodity rents, which enable the combination of strategies involving coercion and buying loyalty.

Most likely, the choice between the path of classical hyper-politicisation and the preservation of hybrid hyper-politicisation will be determined by the challenges faced by the regime. If faced with economic downturns or failures on the frontlines, the regime may be pushed towards greater hyper-politicisation, involving increased repression, stricter demands for citizens to demonstrate their loyalty, and attempts to create a mass party where membership could open doors to 'career growth.' However, achieving success in moving in this direction is not guaranteed. In China, totalitarian institutions have been preserved as a legacy of communism and were not created ad hoc. Additionally, the ideology of anti-liberalism in its current manifestations does not possess sufficient potential for mobilisation and does not necessarily contradict the goals of 'private enrichment.' However, the transformational potential of a protracted war of conquest, engaging society in a traumatic duality of sacrifice and complicity in crimes, may be underestimated. Moreover, the anti-Ukrainian ideology of Putin's regime is increasingly drawing comparisons to fascism and Nazism, which are becoming even more substantiated today.