Regime of Imperial Paranoia: War in the Age of Empty Rhetoric

The decline of ideologies and the paranoia of a despot

The ongoing conflict in Ukraine is characterised by a complete absence of apparent meaning. Commentators seek to interpret it in many ways, some have looked to Russia's imperial ambitions, others to Putin's personal hatred of Ukraine, and others still to the Russian president's insanity. At the outset of the war, it was clear that even members of Russia's Security Council were incapable of understanding what was going on. The failure to comprehend the origins of the war also explains why world leaders, including Volodymyr Zelensky, were unable to believe that the war would occur even right up until it began.

This is, in my opinion, linked to the decline of ideologies. The secularisation of religious teachings is the primary source of ideology. Ideologies emerge as religions fade. It is not difficult to identify the eschatological origins of Marxism or Nazism in their subjugation to a future ideal — communism or the Reich of a Thousand Years. Between the end of the eighteenth century, with its concept of progress and reason, and the end of the twentieth century, however, the promise of ideologies may have been exhausted. Today, the spectre of these ideologies remain in the meaningless notion of expansionism.

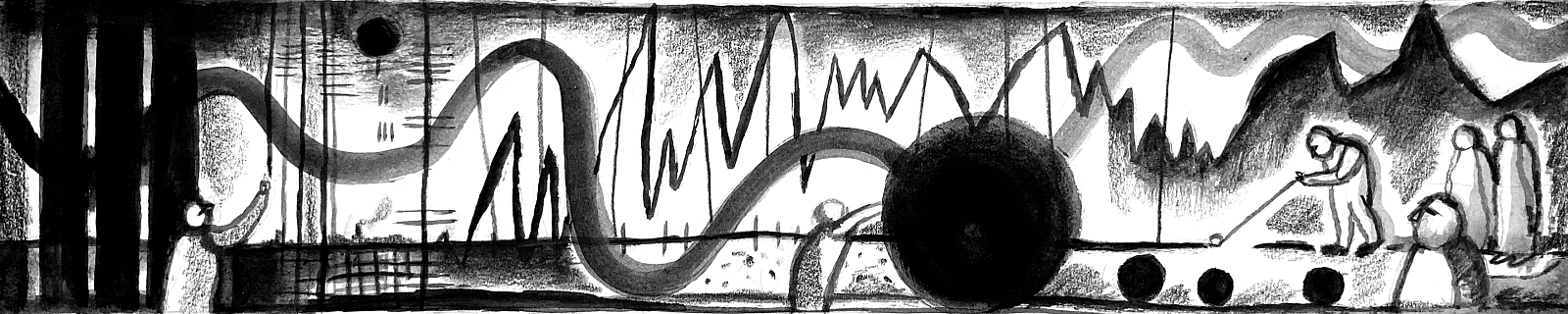

In his seminal article Two Regimes of Madness, Gilles Deleuze identifies one of these regimes as imperialism. It is characterised by the infinite expansion of paranoia. The paranoid imperial regime is built on the unfolding of an infinite sequence: ‘one sign defers to other signs, and these other signs to still other signs, to infinity (irradiation, an ever extending circularity)... Such is the paranoid regime of the sign, but one could just as well call it despotic or imperial.’ Deleuze asserts that this paranoid society is dependent on a 'signifier of the despot' who develops chains of the neverending transmission of signs: ‘there is the great signifier, the signifier of the despot; and beneath it the infinite network of signs that refer themselves to one another. But you also need all sorts of specialised people whose job it is to circulate these signs, to say what they mean, to interpret them, to thereby freeze the signifier: priests, bureaucrats, messengers, etc.’

This structure generates the illusion of significance. It is completely exhausted by the repetition and reproduction of the despot's nonsense. The primary effect of such a system is that repetition functions to produce feelings of loyalty, devotion, and inclusion rather than meaning. No one can explain the meaning of the war, but it is possible to keep on stretching this chain of signs ad infinitum so that, when they reach their imagined limits, they hold the promise of meaning. However, this never happens. What occurs is an outward expansion of the signs to encompass an ever larger group of people. And, while this paranoia produces only the endless repetition and replication of incoherence, it is pervasive, leaving no room for silence or evasion.

The illusion of sovereignty and the multipolar economy

War has neither explanation nor meaning. In its role as the quintessence of meaninglessness, however, it paradoxically organises the world as some type of fictitious constellation of meaning. By its very nature, semiotics is oppositional and dichotomous. And, it is precisely this dichotomy that has just vanished from the discursive landscape.

The political scientist Zaki Laïdi published The World Without Meaning in 1994. In it, he defines the process by which political opposition is gradually erased, which he terms globalisation. Globalisation is the widespread substitution of economics for politics. And the economy is built on principles that are semiotically very different to imperial paranoia. Capitalism develops as a complex interconnected web. In place of the continual monotonous transmission of the signifier of despotism, we have a network structure with a myriad of nodes and connections that are in no way defined by binaries. These are relationships generated by desire, consumption, and trade.

Clearly, such a system cannot provide stable or even coherent meanings. Consequently, since the fall of the Berlin Wall, a pervasive sense of meaninglessness and disorientation has gripped the West. Putin speaks frequently about a multipolar world, but the future he genuinely desires is a binary one. The dominance of today's global economy is the real multipolar world. It is based on decentralisation, which leads to the global deterioration of nations and politics. This results in the decline of old power structures, which are inextricably linked to the formation of meaning. Laïdi formulates this unequivocally, when he writes: ‘Power is nothing when it has no meaning.’

The Russian revolt against the universal rules of the world order might be viewed as a protest against this economic dominance by a state with a weak and uncompetitive economic base. It is an attempt to offset the weak power of economic giants with a mirage of sovereignty and a mirage of meaning (historical, mythical, etc.) Such a confrontation relies on the army, the traditional embodiment of the very idea of power. Russia wants to confront Western economic expansion. The more Russia views imperial paranoia to be built on soft power rather than hard force, the greater its desire to oppose it.

The peculiarity of the current situation is that a disintegrating empire can only be reconstructed via discursive production and repetition. Moreover, rebuilding this empire from its ruins is utterly impossible, since Russia has long been infected with the disease of ‘globalisation’. In any case, the average Russian has long since made a home in the world of capitalist consumption and is well-integrated into the network of microcentres of desire. At the same time, the Russian state lives on as some sort of imperial chimaera and is betting heavily on the fetish of ‘despotic signification.’ In this context, it is symptomatic that Russia's middle class appears painfully aware of the obstacles obstructing the path to the 'centres of desire' in the West, while Russian ideologues advise them to settle in the nonexistent Eurasia of imperial paranoia.

Russian heterotopias and the return of binarity

It seems to me that Foucault’s conceptualisation of the “heterotopia” can be used to describe Russia, and its falling out with the world and modernity. The odd geography of the heterotopia encompasses locations that deviate from the norm of social existence. These include the active conflict zones and unrecognised territories that have surrounded Russia in recent years. However, they could also include fictitious non-existent territories, such as Dugin's Eurasia. In 1967, Foucault coined the term heterotopias to describe odd spatial formations in which normativity is not just violated, but turned inside out.

These bizarre spaces, which lie between the phantom and the reality of violence, are in fact zones of deviance, where the rules of economics, law, politics, or philosophy no longer apply. Just the pure phantasm of sovereign power. In this light, the confluence of the Russian army with criminals, best illustrated by the overtly heterotopic creation of Wagner PMC, is particularly illuminating. The heterotopias created by Russia consistently reproduce criminal communities, while claiming to be magnificent models for the future.

Simultaneously, these meaningless islands of ‘horror’ claim to be able to give meaning and thus a political dimension to the multipolarity of the capitalist society, which suddenly has an ‘enemy.’ The existence of an adversary gives the illusion of duality. This should be considered alongside Carl Schmitt's theory that politics emerges when an adversary exists, and that the enemy is a central term in politics. The Russian heterotopia enables the world to discover unity and purpose. If the purpose of the conflict remains unclear to the Russian people, it is becoming clearer to the rest of the world. In the eyes of economic civilisations, Russia identifies as a ‘barbarian,’ an ‘other,’ and a deviant on principle.

It was not so long ago that it was believed that the West would never apply severe sanctions on Russia, as doing so would be counter to its economic interests. The West could not leave its citizens without gas and heat. It was believed that corporations would never exit the Russian market because they would incur enormous financial losses. And so on. Perhaps unexpectedly, the economy is becoming less important everywhere except in Russia. In its stead, there is a kind of ideology. Empty words have given way to a simplified, binary view of the world. The West has suddenly acquired a capacity for action, whereas Russia appears to be totally devoid of such. The ability to endure discomfort and loss in the name of ideology and morality has emerged in the West, not in Russia.

For the time being, the Western world has risen above the insignificance of pure economic concern. An incarnation of pure evil appeared, and this necessitated mobilisation. This moral ‘simplification’ of the world, however, is based on a somewhat childish vocabulary of fairy tales and fantasy that permeates the media. In Ukraine this is, understandably, particularly clear, evident in the use of terms like orcs, Mordor, Voldemort etc. In the meantime, the Kremlin adopts a James Bond aesthetic (such as Putin's kilometre-long desk or Solovyov's comical French tunic, which appear to jump out from the screen).

Linguistic junk and the imitation of mobilisation

Deleuze, when describing the regime of imperial paranoia, underscored the necessity for persons ‘whose job it is to circulate these signs, to say what they mean, to interpret them, to thereby freeze the signifier’. This refers to the endless production of words that have no relation to reality. And this is one of the most remarkable characteristics of Russian society, where the speaking and creation of signifiers have expanded to unfathomable proportions. In these poetics of verbal garbage, nonexistent Nazis are executing a genocide on the Russian people, and Russia is not attacking Ukraine, but rather responding to its aggression, etc. The signifier is quite literally heterotopically reversed.

Kierkegaard once penned the incisive book Two Centuries, in which he may have been the first to emphasise the issue of the vast production of linguistic junk (snak in his vocabulary, and in the English translation, chatter). Kierkegaard distinguishes between two epochs: the age of revolution and the ‘present age.’ The age of revolution is an ideological and hence meaningful age. He states that existence within it is accompanied by passion and, thus, ‘has form.’ An important feature of the age of revolution was enthusiasm, which Kant believed to be the most important revolutionary affect. The current era is bereft of creativity and zeal; it has been submerged within a superficial absence of genuine action. Kierkegaard writes about vis inertia, or the force of inertia, as the dominant factor. The most significant characteristic of the present period is that it continues to imitate an age of authenticity, passion, and action. All of this, however, is being entirely transformed into a form of social theatre.

And the more illusory the order, the greater the number of words produced for its false preservation. It is common knowledge that corruption is the core of the Russian state. However, the greater the depth and brazenness of corruption, the more patriotic the remarks of crooks and bribe-takers. Like Novorossiya or the Russian Empire, linguistic junk creates a facade of social fiction. The extreme persistence with which the Russian Federation's leadership has refused to label the conflict a war is indicative of this. War necessitates mobilisation and a shift in the way of life. And this is precisely what marginal radicals such as Girkin desire. But those in power are well aware that society lacks the capacity for mobilisation and is only capable of Kierkegaardian snak.

This incapacity to mobilise its population is a fundamental distinction between the Russian state and the truly totalitarian regimes of Stalin and Hitler. They were able to wage war and to mobilise their people. Hannah Arendt wrote that without movement and mobilisation, totalitarianism is impossible ‘...the idea of domination was something that neither the state nor a mere apparatus of violence could ever achieve, but only a movement sustained in perpetual motion, namely the constant domination of every single individual in every single sphere of life.’

In a regime of imperial anxiety, the incessant proliferation of signifiers comes to serve as a simulacrum of mobilisation, while simultaneously preserving complete social passivity. At the same time, the consumer culture of Russian society is revealed by the fact that money, not ideology, is unhesitatingly stated as the primary motivator for soldiers. Money is the final refuge of waning enthusiasm. Because of this, looting has become a symbol of the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

Putin's universe is one of complete stability that is developing into paralysis. And this repressive stability is oddly consistent with military expeditions, which are only acceptable insofar as they fit within this apparent immobility. Thus, regardless of what occurs on the front, the war will continue to be referred to as a ‘special military operation’ — a purely theatrical war simulacrum. No matter how much the front collapses, the authorities will pretend that the military operation and social immobility are one and the same thing. Putin's unveiling of a ferris wheel in Moscow just as the front was collapsing near Izyum was no coincidence. A wheel spinning in place without purpose is the perfect metaphor for the current state of affairs.

Samuel McCormick, who has conducted an in depth study into chatter, found that its emergence coincides with the rise of industrial society, with its devotion to perpetually operating machinery and spinning wheels. It has been repeatedly noted that in industrial society, it is not the tool that is subordinate to man and his needs, but in reality things are to the contrary. The machine, whose inactivity would be catastrophic, must continuously operate and generate, thus transforming from a means to a purpose. As long as the machine continues operating, the average citizen must purchase the product, even if they do not require it. It is the same with speech, which gets converted from a communication tool into a meaningless end in itself. This is indicated by the ease with which semi-mechanical trolls or automated bots have been integrated into this process of communication.

War as a rhetorical phenomenon

In a context where binaries and meaningful communication are vanishing, rhetoric comes to the fore. It is a method of organising meanings through an infinite system of analogies, transpositions, rhetorical approximations, etc. Rhetoric operates according to antinomies, not oppositions. An antinomy is something that cannot be reconciled or brought together. Rhetoric is the mechanism by which the heterotopia is produced, and which, according to Foucault, ‘has the potential to unite in one physical place several incompatible realms.’

At this very moment, rhetoric is playing a significant role. Even more so given that its area is that of persuasion and not the domain of meanings. The meanings lose significance and recede into the world of mythology. And this is evident in the discursive landscape that has developed in Russia. In this discursive arena, the accompanying concepts and ideologies have long since vanished from reality. They have entered the heterotopia of victory over Nazism or Eurasianism, which are merely rhetorical worlds. Ultimately, Eurasia is nothing more than an imaginary region of rhetorical encounters and substitutes. The already deceased Novorossiya is a similar heterotopic myth.

An intriguing aspect of the current situation is that this myth has found itself approaching something like reality in the war. This is something that Putin, of course, did not want, believing that he would be able to limit the war to yet another work of fiction. However, fiction has taken on the characteristics of reality. And what was originally intended to be a merely rhetorical construct, snak, has begun to take on a simple, even simplified meaning.

This is reminiscent of Euripides' story of Helen the Beautiful. Euripides says that Hera, at Zeus' request, created a cloud eidolon — a simulacrum of Helen — which was stolen and taken to Troy. However, Helen actually lived in Egypt and had never stepped foot on Trojan soil. Instead, at the core of the conflict was an illusion. The eponymous character in Euripides' tragedy Helen tells of Zeus who made ‘me an object of unhappy strife 'twixt Hellas and the race of Priam. And my name is nothing but an empty sound among the Simois streams ‘. As such, all the years of devastation depicted by Homer were caused by a Kierkegaardian snak, a ‘sound without reality.’ Helen appears to me to be the perfect analogy for the current situation. Gorgias of Leontini, to whom Plato dedicated a dialogue of the same name, wrote a rhetorical text that has partially survived to this day — The Praise of Helen. This text is regarded as an example of an encomium and a demonstration of the effectiveness of rhetoric. Gorgias defines it as an epideictic speech based entirely on the rhetorical craft itself. It appears that the only content in this encomium is the demonstration of rhetoric.

The spectre emerges from nothing and becomes convincingly lifelike. Helen, who was considered the embodiment of wickedness because she cheated on her husband and thus brought about a terrible war, is presented by Gorgias as a model of faithfulness and virtue. This metamorphosis is founded in the figurative nature of language, which has the ability to convert reality into anything.

Ritual: the unity of belief and disbelief

The functioning of civilization is rooted in rituals, not in a coherent system of concepts and beliefs. The anthropologist Roger Keesing endeavoured to determine the meaning of the fundamental anthropological term 'mana'. We know of this term from Marcel Mauss ( it is an all-pervasive mystical force known among 'primitive' societies). Numerous interviews with members of relevant cultures led Keesing to the conclusion that no one understands the precise meaning of these terms that have vital cultural significance. The meaning of such an undefinable notion develops at the intersection of many discursive frameworks. People discover the meaning of these notions in a variety of pragmatic contexts. And these attempts to make meaning are typically rituals.

According to Maurice Bloch, ritual weakens and formalises syntactical freedom of speech. Hence rhythm holds particular importance within rituals, including singing, dance, and repetition. Rhythmic repetition creates the appearance that the sought-after meaning has been strengthened, as if it has been ‘inflated’ by this formalisation.

In this context, it is important to evaluate the growing significance of celebrations in Russian culture. I am of the opinion that this should be viewed as an indication of a morbid ritualisation which has formed around the void of meaning. The more extravagant the celebrations of past victories, the clearer the transition towards ritualistic performativity. Instead of faith in ideas, a half-belief in appearances has emerged, which is characteristic of rituals.

Pierre Smith, a Belgian anthropologist, has written that rituals are constructed around a sort of focalised core surrounded by symbols. In the Eucharist, for instance, this core is when the wine is transformed into blood. Smith argues, however, that no one believes that the wine they are drinking is the genuine blood of Christ. Smith describes a conversation with a Senegalese Bedik tribe ceremonial initiator. The ritual participants must act as though they sincerely believe. And if any of them exhibits scepticism or questions the rite, they must be punished harshly. But if one of the participants believes too strongly and enters a frenzy, this may be even worse and just as damaging to the ritual.

Both sceptics and those who believe whole-heartedly in empty words, including terms like neo-Nazis and extreme nationalists, are incompatible with the culture of ritual speaking that Russia is becoming. Rituals require constant rhetorical swings between believing and scepticism. This ambiguity makes it possible to bind into some sort of cultural unity the variance of elements that do not fit into dichotomies or frameworks of meaning.This, I believe, should be considered by sociology and political science, two fields that claim to comprehend society yet are notoriously poor at doing so. Occasionally, these disciplines seem to generate Helen-like apparitions. In actuality, the ‘logic of regimes’ and ‘people's opinions’ are merely rhetorical and ritualistic uncertainties.

Whenever sociologists discuss public support for the Putin regime's policies, they are confronted with an unanswerable question. Within the context of social rituals and meaningless discourse, even a person who has drawn the letter Z on a car or a fence finds it difficult to say whether they support the war or not. Victor Turner famously introduced the concept of ‘performative reflexivity.’ He stated that in traditional communities, when the need for self-reflection is lessened, individuals represent themselves via rituals and gain an insight into who they are as a result. The extent to which modern Russian society is fixated on a theatrical interpretation of its own triumphal indestructibility, utilising performative reflexivity to speak away their doubts in a trance-like state, is readily apparent.

While thousands of people are dying on the front lines, there is a widespread theatricalisation of imperial greatness. Imperial paranoia has progressed from the fabrication of interminable meaning chains to the elimination of reality itself. The letter Z zigzags and sews together a frail transient connection between pseudo-enthusiasm, increasing uncertainty regarding the future, and fear in the face of escalating hopelessness.

Read more

The current stage of the state's ideological expansion is designed, on the one hand, to definitively exclude and 'cancel' the liberal segment of Russian society, and, on the other hand, to change the identity of that part of society that absorbed the ideological opportunism of the 2000s, thereby neutralising the value baggage and liberal aspirations of the perestroika and post-perestroika era.

The current stage of the state's ideological expansion is designed, on the one hand, to definitively exclude and 'cancel' the liberal segment of Russian society, and, on the other hand, to change the identity of that part of society that absorbed the ideological opportunism of the 2000s, thereby neutralising the value baggage and liberal aspirations of the perestroika and post-perestroika era.

Why Putinism Is (Still) Not An Ideology

Ideologies usually create a kind of political map that can be used to understand where political processes are heading. However, Putin has long and successfully avoided ideological clarity, which has enabled him to maintain a certain political intrigue around his key decisions. This characteristic of the regime persists today: the Kremlin can neither explain the reasons and goals of its war in Ukraine nor ensure ideological mobilisation in support of it.

Why Putinism Is (Still) Not An Ideology

Ideologies usually create a kind of political map that can be used to understand where political processes are heading. However, Putin has long and successfully avoided ideological clarity, which has enabled him to maintain a certain political intrigue around his key decisions. This characteristic of the regime persists today: the Kremlin can neither explain the reasons and goals of its war in Ukraine nor ensure ideological mobilisation in support of it.

Does the Putin regime have an ideology?

The ideology of the Putin regime is resilient because it responds to the existing demands of the population, draws on deeply rooted Soviet traditions, and at the same time fills the ideological void that emerged after the collapse of the Soviet Union. This will help to sustain the Putin regime for many years to come.

Does the Putin regime have an ideology?

The ideology of the Putin regime is resilient because it responds to the existing demands of the population, draws on deeply rooted Soviet traditions, and at the same time fills the ideological void that emerged after the collapse of the Soviet Union. This will help to sustain the Putin regime for many years to come.