The Lonely Gas Station: Why the Putin era has doomed Russia for economic failure

'We were told some time ago, with fingers pointed at us, that we are a “gas station”, not an economy, but now “all that is changing”, we are becoming “self-sufficient” Vladimir Putin declared during a meeting with representatives of the Public Chamber a few days ago, eager to convince the audience that this moment had arrived in the twenty-fifth year of his rule.

I was curious to see if Russia really has ceased to be a ‘gas station’. At present, I cannot reach out to Putin's speechwriters to understand how they arrived at such a conclusion. However, at Harvard University's Kennedy School, there is a Growth Lab, which for many years has been comparing the levels of technological development of various countries (currently they look at 132). The lab uses its own database to construct an Index of Economic Complexity, which is based on the structure of a country's goods exports. Following in the footsteps of Adam Smith and David Ricardo, unlike Vladimir Putin, the scientists at Harvard believe that the wealth of nations is created through the division of labour, and no economy can be successful if its goal is self-sufficiency, i.e., autarky. They assign different levels of technological complexity to all the items in a country's export basket for analysis and comparison, ultimately calculating a composite index according to which countries are ranked.

The data from Harvard's Growth Lab reflects changes from 1995 to 2021, and for my analysis, I chose the year 2000 as my starting point, as this was when Putin became Russia's president. Data for the period since the onset of the current war is not present here; however, I would not expect any significant changes in the technological complexity of exports under the conditions of war or sanctions.

'Petrolheads' and 'like-minded' countries

I will begin by discussing other 'gas stations', countries whose export structures rely heavily on raw materials. This group includes both developed nations (Australia, Canada, Norway) and Russia's counterparts in the oil curse (Iran, Saudi Arabia, Kazakhstan). The graph clearly displays how volatile global commodity prices led to shifts in export structures, with almost all these countries sliding down the global 'economic complexity' rankings, signifying that their experts became less technologically advanced.

Economic complexity index, 2000–2021

After 2015, when oil prices stabilised between $70–90 per barrel (discounting short-term deviations on both sides), countries began to climb up the ratings ladder. Against this backdrop, Russia's ascent was not particularly impressive; the country only partially recovered its losses and dropped 25 positions in 2021 compared to 2000. For comparison: Saudi Arabia rose 25 places during this period, Iran was up 33, while Kuwait and Oman, not depicted on the graph, climbed a striking 53 and 55 positions, respectively. However, it was in good company in the 'less fortunate' group: Norway (–13), Kazakhstan (–16), Canada (–19), Australia (–33).

Thus, Russia can be said to have retained its position in the 'gas station' rankings, albeit with a caveat. If Russia's climb up the rankings post-2015 was entirely linked to changes in global commodity prices, Saudi Arabia's success was tied to building up its colossal oil processing capacities. Unlike Russia, which stopped at petroleum production, Saudi Arabia has ventured into petrochemicals, compensating for declining oil extraction with higher added value.

The next group of countries are 'like-minded', including the members of BRICS (Brazil, China, India, South Africa), to which I have added Belarus and Turkey. This group is also divided into 'underachievers' (Brazil, Russia, South Africa), 'high performers' (China and India), and those 'holding steady' (Turkey and Belarus). The 'high performers' are rather self-explanatory. China has long been the world's factory, claiming 28.5% of global manufacturing. To sustain economic growth, it needs to shift to value-added sectors, but there it faces stiff competition from technological leaders (more on them below). Although India has achieved high growth rates, it has yet to become an export-oriented economy, and without this it cannot rapidly ascend the rankings.

Economic complexity index, 2000–2021

The problems of the ‘losers’ differ in shades, but across the board, there is a common thread of lack of rule of law, corruption, and differing degrees of authoritarian rule. Those ‘holding steady’ - Turkey and Belarus — are united not only by their stable position in the rating over the last fifteen to twenty years, but also by the nature of this stability. Belarus' high position is determined by the large volume of food and engineering exports to Russia, a feature of its economy inherited from the Soviet era. Turkey's ascent in the late 1990s to early 2000s was tied to its movement toward the European Union. However, Erdogan's rise to power put an end to this process, and now Turkey's economy is struggling to preserve its 'European' heritage from the turn of the century.

Generally speaking, ahead of struggling South Africa and Brazil, Russia has barely improved its position since 2010 and is losing not only to China and Turkey, which overtook it in the 2000s, but also to India, which has moved up fifteen places in the economic complexity index since 2010. Russia is clearly falling behind its 'like-minded' counterparts in the competitive arena, and it is unclear what steps it can take to appear more successful.

The League of Success

Now, let us take a look at the group of 'technological leaders', in which I have included some countries from the top twenty: Japan, firmly holding the top spot, South Korea, the United States, Hungary, Romania, Mexico (I have excluded Germany, Switzerland, Austria, and the United Kingdom from the top ten to avoid cluttering the graph). I have added Vietnam to this mix.

Economic complexity index, 2000–2021

To say that Russia is not among the leaders is an understatement. This conclusion is glaringly obvious, and one does not need Harvard's data to recognise it. The most interesting thing that can be seen in the third graph is how quickly the situation can change over the course of twenty-five years, i.e. within the course of a single generation.

We can see Vietnam's rapid ascent, surpassing Russia and becoming the most attractive destination for foreign investors in Southeast Asia. We see South Korea and Hungary steadily climbing upwards, Mexico confidently holding its ground in the 'big leagues’. Mexico, which was categorised as a 'gas station' until the early 1990s, has firmly tied itself to American manufacturing after the depletion of its 'black gold' reserves and signing of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), becoming the world's tenth-largest industrial producer. There have been numerous success stories over the past twenty-five years, tales of progress in Romania (+21 positions, ranking 19th), Thailand (+14, ranking 23rd), Estonia, and Lithuania (+14 and +19, ranking 27th and 30th, respectively).

What conclusions can be drawn from this? First, alas, Russia remains a global 'gas station' and shows no signs of changing this status. Second, even among the 'gas stations,' Russia cannot boast remarkable achievements, as it is firmly stuck at the initial stages of processing its raw resources. Third, the mere possession of natural resources is not a guarantee of nor a hindrance to success. Look at the abovementioned Arab countries, add the Emirates (+25 positions) and Angola. But do not forget to consider Argentina (–20 positions), Azerbaijan (–40), and Venezuela (–53). In short, being a 'gas station' provides resources, but how a country utilises these resources depends on the ambitions and desires of its ruling class.

Last, but not least, in this race, there are no eternal losers. Each country sooner or later gets its chance, which can either be seized or missed. Over the last twenty years, the Russian economy has received $3.5 trillion just because of rising global oil and gas prices, of which a very small portion went towards building potential for future development. This portion was so small that Russia has not been able to alter its export structure or learn to produce anything the rest of the world needs other than raw materials. I would like to believe that very soon, by historical standards, Russia will have another chance, and whether we take it or not depends on us.

In the pursuit of success, ‘self-sufficiency’, and downsizing

Here, an astute reader must pose some key questions: what defines successful change and how can it be achieved? The answers are to be found in the economic success stories of developing economies over the past forty to fifty years, where globalisation has enabled some to exploit newfound opportunities and locate their niches within the global division of labour. This is because no country today can sustain complete self-sufficiency — producing everything it needs for itself. Much is produced more affordably elsewhere due to the accessibility of diverse resources (natural, financial, human), advanced technologies, or successful industrial policy programs.

Often, the minimum scale of efficient production for a single commodity is impossibly vast, even for a major economy. For example, after the 2008 crisis, it became clear that the minimum production volume for a sustainable car company is 5 million cars per year. After that, it became clear that the Russian AvtoVAZ, even at full capacity (1.4 million cars per year), would not be able to compete on the world market in any class of cars. However, as part of the Renault-Nissan-Mitsubishi alliance, it became an organic element of a globally competitive company.

The secret of long-term rapid growth (outpacing global economic growth at 5-8% annually) has long been established: an outward market orientation and the establishment of an export-oriented economy. Therefore, surpassing GDP growth through export expansion can be deemed a good indicator of successful changes.

To illustrate this point, I will use graphs made by the Harvard researchers to depict the growth of exports in Mexico, Hungary, and Romania, which I have already mentioned above. These graphs clearly show, firstly, that in all three countries the rapid growth of exports went beyond the sectors that were its traditional mainstay (raw materials, agricultural products, textiles). While these sectors grew, their expansion was incremental, not exponential. Additionally, an integration factor is noteworthy: for Mexico, it was the NAFTA agreement, leading to a southward mass migration of enterprises from America; for Hungary and Romania, it was EU accession, which also led to a rapid growth in exports of services.

Dynamics and structure of Mexico's exports, 2000-2021 (1.7-fold GDP growth), billion USD

Dynamics and structure of Romania's exports, 2000-2021 (2.2-fold GDP growth), billion USD

Dynamics and structure of Hungary's exports, 2000-2021 (2-fold GDP growth), billion USD

In all three cases, the decision regarding which export-oriented enterprises to establish, where to locate them, and with whom to build technological and organisational partnerships lay with the 'invisible hand of the market' — a task beyond the reach of any central planner. However, the outcome reveals a marked surge in exports across different sectors.

An example of altering export structure through state industrial policy is Saudi Arabia. After 2008, when hydrocarbons accounted for 90% of exports, the country initiated an advanced petrochemical programme, which has gradually borne fruit. However, this model of structural adjustment does not allow the achievement of overall export growth. However, a comparison between Saudi Arabia and Russia clearly demonstrates the results of Putin-era economic policies: fluctuations in export volumes are related to the dynamics of oil prices and slow growth in exports of precious metals and stones, but there are no changes in the structure of exports.

Dynamics and structure of Saudi Arabia's exports, 2000-2021, billion USD

Dynamics and structure of Russian exports, 2000-2021, billion USD

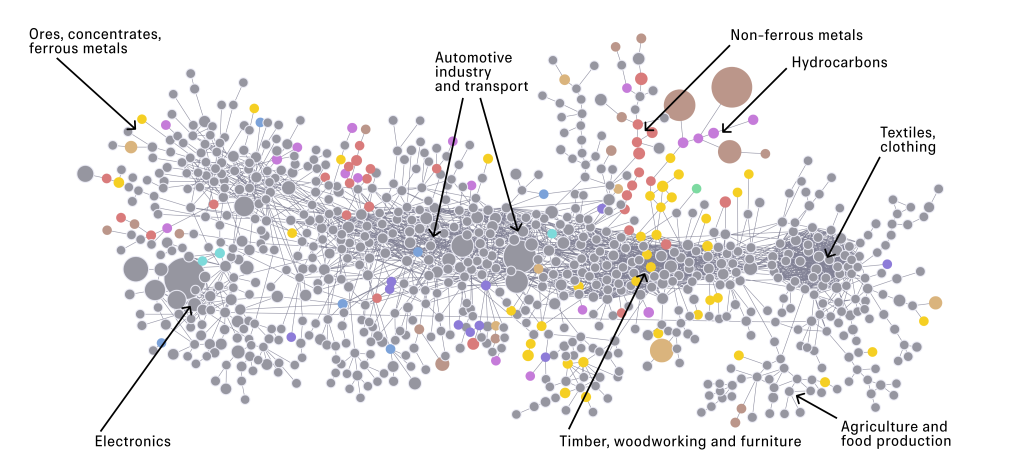

This question can be approached from the opposite direction: What does a country's place in the global division of labour look like as a result? Here again, I will use the help of the Harvard team, who have visually depicted industrial clusters and centres of value creation in the global economy. If the corresponding circle on the 'map' of global production clusters is shaded with a particular colour, it signifies that the economy of that country exports the corresponding products. If the circle is not shaded, it indicates that it has not yet reached this point.

Map of Russia's exports as a share of global production, 2021 ($560bn)

Map of Romania's exports as a share of global production, 2021 ($122bn)

.png)

Map of Hungary's exports as a share of global production, 2021 ($167bn)

.png)

Map of Mexico's exports as a share of global output, 2021 ($537bn)

.png)

Here, a clear picture emerges: Russia's economy is, with few exceptions, on the periphery of global trade, persistently remaining a provider of raw materials, i.e. it is effectively a 'gas station'. The core of the 'world map' remains unexplored by the Russian economy, primarily marked in a dense grey, signalling a lack of any economic foothold. Moreover, if we look at the similar scheme from 2005, we can conclude that Russia's involvement in the global division of labour has only decreased since that time.

The Growth Lab data used for this analysis does not provide information about the technological levels of production for domestic consumption. However it is possible to infer that the transformation of Russia into a 'self-sufficient' economic power implies technological downshifting. If today the Russian economy cannot produce technological goods that compete in the global market, achieving 'self-sufficiency' would require the use of less efficient or outdated solutions that are not in demand worldwide.

On the other hand, Russia's role as a major exporter of raw materials has fortified its economy against severe Western sanctions. In other words, this economic structure is useful for the Kremlin, allowing it to sustain its war in Ukraine. However, the inevitable preservation of this economic structure, reinforced by restrictions on access to modern technologies, will make it harder and more expensive to modernise this structure after a shift in political priorities.