Catching up with the Crisis: Will the sudden decrease in export revenues in December herald a new period of tension in Russian finances?

In December, the Russian budget unexpectedly lost 200 billion rubles in oil and gas revenues, which was fuelled by falling oil prices and problems with the supply of Russian oil to India. Indian authorities explained their refusal to accept Russian tankers as a result of tougher sanctions. Another reason for this was the changing dynamics of the global oil market, which, according to forecasts from the International Energy Agency, may become surplus in 2024. If this happens, discounts on toxic Russian oil will rise again, and the Russian budget, inflated by military spending, will be short of income.

However, balancing it through the devaluation of the ruble will not be so simple. As the assessment of the balance of payments for 2023 published by the Central Bank shows, the current account balance is at its lowest. This is a result of the fact that the Russian economy has become more import-dependent as a result of sanctions and the war. Devaluation will make imports more expensive for Russian producers and for the budget. An alternative way to cover the deficit is to spend the resources from the National Welfare Fund. But, with the price of Russian oil around $50 per barrel, it will not be enough for more than two years. Thus, in 2024, the Russian economy will still face the macroeconomic effects of sanctions, which were previously offset by the crisis-driven growth of energy prices and Russian export revenues.

The Russian budget deficit in 2023 unexpectedly exceeded the government's forecasts by almost 300 billion rubles, totalling, according to the preliminary assessment by the Ministry of Finance, 3.2 trillion, or 1.9% of the GDP. The increase in the deficit does not appear to be critical; rather, experts and markets were impressed by the fact that, back in December, Finance Minister Anton Siluanov confidently reported that the deficit would not exceed 3 trillion rubles. Against this backdrop, such a drastic change in the projected figures was perceived as a bad sign. The main reason was the shortfall in oil and gas revenues, which in December fell almost 200 billion rubles below expectations. This was likely influenced by relatively low prices for Urals crude, damper payments to oil companies, and a reduction in purchases of Russian oil by India, suggests Olga Belenkaya, the head of the macroeconomic analysis department at Finam.

Indeed, according to reports from the Russian Ministry of Finance, the price of Russian Urals crude fell to $64.2 per barrel in December, down from $70.8 in November, and the return of damper payments, which the government tried but failed to reduce, was an additional blow to oil and gas revenues. In total for 2023, they amounted to 8.8 trillion rubles, slightly less than the budgeted plan, which envisioned basic revenues of 8 trillion and additional revenues of 0.94 trillion. Throughout the year, oil was cheaper than the government expected: $63 instead of the anticipated $70 per barrel of Urals crude. However, the weakening ruble (the budget was planned based on 68.3 rubles per dollar) compensated for this. Nevertheless, the rebalancing of revenues through a slightly greater depreciation of the ruble and the return of damper payments were entirely predictable in December. Therefore, the deficit in December is apparently linked to the decline in prices and issues with Indian shipments, which seem to be connected phenomena.

Problems with shipments to India, which became the largest importer of offshore shipments of Russian oil last year, arose back in November. In December, according to Kommersant, not a single tanker with Russian oil was unloaded in India. According to Bloomberg, some of those shipments were diverted to China. Indian Oil Minister Hardeep Singh Puri attributed the halt in purchases to sanctions: 'It is about the price cap [of $60 per barrel] and the restrictions imposed on [tankers used by Russia].' He also said that 'If the price of Russian oil does not meet [the price cap], India will buy oil from Iraq, UAE, and Saudi Arabia.'

Sanctions pressure is indeed intensifying. The first sanctions against violators of the price ceiling were imposed in October of last year. However, new sanctions have been introduced regularly since then. On 18 January, the US Treasury Department imposed new restrictions, this time against 17 tankers carrying Russian oil under the flag of Liberia, as well as the UAE-based company that owns them. Further, on 20 December, the US Ministry of Finance published new rules for monitoring compliance with the price cap.

However, it is not just about sanctions. The Indian minister's reservations are quite telling: in essence, it is a demand for a reduction in the price of Russian oil, backed up by the threat of replacing it with oil from other countries. This demand and threat, in turn, indicate changes in the oil market — it no longer appears to be in a deficit.

The January forecast from the International Energy Agency (IEA) does not predict price growth. The growth in global demand in 2024 will slow from 2.3 million barrels per day in 2023 to 1.2 million. Weakness in the global economy and, at the same time, an increase in its energy efficiency continue to exert pressure on demand. Additionally, the agency has also revised its oil supply forecast. AJust a month ago, it expected a growth of 1.2 million barrels per day in 2024; now it is projecting 1.5 million. This increase will be largely provided by the United States, Brazil, Guyana, and Canada. Moreover, the IEA expects that Saudi Arabia and Russia will gradually abandon some of their voluntary production limits. In such an instance, the oil market will become surplus. OPEC+ traditionally assesses the global situation more optimistically for oil producers. AAccording to the organisation's expectations, consumption growth in 2024 will be 2.2 million barrels per day (due to increased demand for air travel and industrial activity in non-OECD countries). But, if the IEA forecast materialises, in a surplus market and amid increased sanctions pressure, discounts on Russian oil will inevitably increase. This poses a serious threat to the ambitious plans of the Russian government, which has drawn up its 'victory budget' based on the average price of a barrel of Urals being $71, with Brent at $85 per barrel. In December and January, a barrel of Brent was priced below $80.

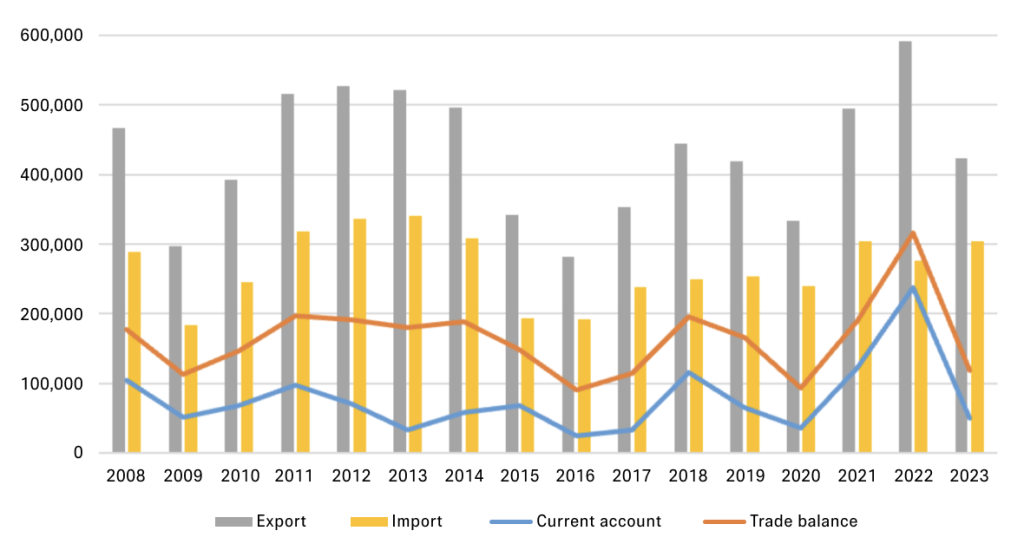

The Central Bank's 2023 balance of payments estimate published on Friday also indicates that Russia has entered a more challenging period in terms of macroeconomic performance. The current account surplus was $50 billion in 2023 and the trade surplus $118 billion; the former is five times less than the previous year, and the latter is two and a half times less.

Key indicators of the balance of payments for the Russian Federation, 2008–2023, million USD

It should be noted that both surpluses are at low levels, comparable to those observed in 2009, 2015-2017, and 2020. However, export revenues in 2023 correspond to the ten-year pre-war average and those of, say, 2019 ($427 billion, $421 billion and $419 billion, respectively). Meanwhile, the import level for 2023 is 15% above the ten-year average and 20% above 2019 levels. This means that, despite talk of import substitution, the Russian economy has become more import-dependent amid war and sanctions than it was in the pre-war era. This was likely fuelled by the increase in import prices due to rising logistics costs and increased transport distances, the need to replace imported equipment due to sanctions and, finally, massive purchases of components for arms production.

In the event of further oil price declines, the Russian economy and government will find themselves caught between two fires. A decline in export revenues leads to a decrease in budget revenues, but their rebalancing through devaluation will reduce the availability of imports and increase budget expenditures on purchases of critical imports and military components. An alternative scenario to support the budget is the sale of funds from the National Welfare Fund (NWF). According to the Chief Economist for Russia and the CIS at Renaissance Capital, Sofia Donets, a $5 per barrel decrease in oil prices reduces the annual revenues of the Russian state by approximately 1 trillion rubles. Since the beginning of Russia's invasion of Ukraine, the National Wealth Fund’s liquid capital has almost halved to 5 trillion rubles. While it used to consist mainly of freely convertible currencies, it now includes less liquid yuan (60%) and gold (40%). To finance the budget deficit in December 2023, 2.9 trillion rubles were used, with liquid NWF funds decreasing from 6.1 trillion rubles to 5 trillion over the year (in dollars, the reduction looks even more significant—from $87.2 billion to $55 billion). The decline in Russian oil prices may force the government to spend the NWF funds faster. They will only last for a year or two if the price of a barrel of Russian oil drops below $50, according to Alexander Isakov, Bloomberg's Chief Economist for Russia.

Subjected to broad Western sanctions after the invasion of Ukraine, the Russian economy was able to leverage its position in the global energy market as a cushion. Sanctions and the threat of supply interruptions boosted global energy prices, resulting in an unprecedented export income for Russia, mitigating the effects of capital outflow and the disruption of import supply chains, as Re:Russia wrote last year, as well as a surge in budget spending. By the end of 2023, however, global energy markets had returned to normal. Falling Russian volumes are gradually being replaced by new suppliers, and the revenue cushion is thinning. If the energy market does not undergo new upheavals, it is highly likely that Russia will now face the effects of sanctions that were offset by the crisis-driven dynamics of the energy market in 2022-2023.